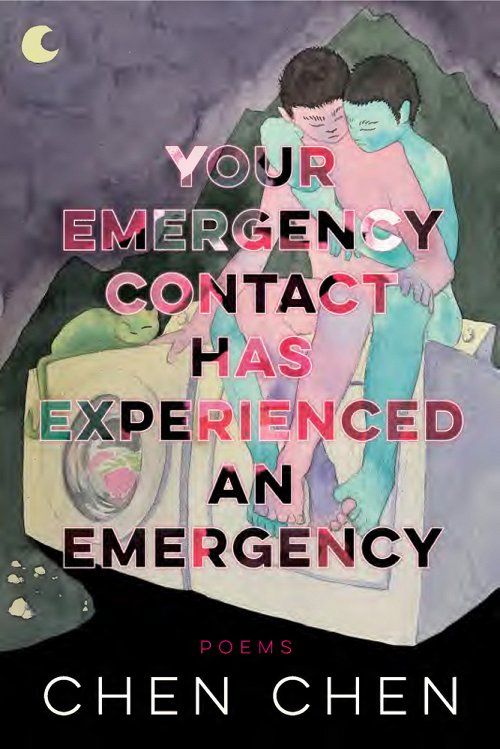

Title: Your Emergency Contact Has Experienced an Emergency

Author: Chen Chen

Released: 13 September 2022

How I Got It: bought from publisher website

Rating: 4 out of 5 stars

Today, I have a slightly different sort of book review for you all. I’m talking about a new poetry collection by poet Chen Chen (author of When I Grow Up I Want to Be a List of Further Possibilities) titled Your Emergency Contact Has Experienced an Emergency.

I read a lot of poetry, but I don’t talk about it much on this site, a fact that I want to try to change. Since I literally just finished reading this one a few minutes ago, I thought I’d go ahead and write up a review while it’s still fresh in my mind and before I have a chance to get distracted by other things and forget to do it.

Chen Chen is a queer Chinese-American poet. The vast majority of his poetry centers on his Chinese-ness and his queer-ness to varying degrees. I really enjoyed his first full collection (When I Grow Up…) and so I leapt at the chance to buy his new one. This book did not disappoint.

The language is sharp and playful and incisive and contemporary. At times delightfully vulgar, and at other times fascinatingly opaque. Chen Chen demonstrates skill and ingenuity with a wide range of forms, from compact carefully constructed tercets to large prose poems that are almost breathless with long momentum to a clever little anagram poem that uses only words spelled from the letters of his name (with the clever addition of the phrase “no middle name” to fill out the severe lack of options in just “Chen Chen”).

I took particular pleasure in the homage to other Asian-American poets throughout the collection, including Justin Chin, Marilyn Chin, Bhanu Kapil, and others. But what I loved the most, probably, was the sheer unembarrassed SPECIFICITY of the poems in this collection.

These are poems for now, vital and relevant in the wake of the pandemic and 2020 shutdown, and in the midst of continued tensions. Many of the poems reference the pandemic, as the narrator faces resurgence of anti-Chinese racism, and invokes never-ending questions that all Asian-Americans face in one way or another: are we ever Asian enough? Are we ever American enough? How can we be both at once, and who gets to decide?

Chen Chen also invokes the specificity, locality, and histories of his own personal life with such unabashed and blunt detail that you feel you might as well be sitting at his dining room table, listening to him talk about his family and his partner and his life. The reader lives with him in Massachusetts, struggling with his mother’s disapproval for being gay; and travels to Lubbock, Texas for grad school, and joins him when he visits China, feeling both inside and outside the culture.

The specificity of “Doctor’s Note” in particular, resonates with me as the note declares: “Please excuse Chen Chen from class. He is currently dead.” This poem goes on to list the ways that Chen Chen has attempted to remedy to situation, including the Coldplay song “The Scientist,” new episodes of Buffy the Vampire Slayer, and Tai Chi in his room. Perhaps not every reader can identify with these specifics, but everyone knows that sensation of being so miserable that all you can do is stay in bed surrounded by the little things you love.

Sometimes the unrelenting detail can be off-putting for the more squeamish: such as in the poem “Winter” in which the narrator contemplates “Big smelly bowel movements this blue January morning” and wonders if the words “shit” or “scat” are “more or less literary than ‘poop’…” Or, in the poem “Ode to Rereading Rimbaud in Lubbock, Texas,” where the narrator describes his “poetics of deep threat & tonguefuck.” These sorts of details might be a bit much for some readers. They make even me squirm a bit in places (and I have a high tolerance), but in the end they only add to the layers upon layers of empathy and emotional resonance that radiate from these poems.

No doubt, the vulgarity can be uncomfortable in places, but it is clearly MEANT to be uncomfortable, and thus shake the reader out of their commonplace experiences). And for every moment of uncomfortable vulgarity, there are dozens of moments of beauty and pathos, as Chen Chen (or the narrator of the poems) showers his lover/partner Jeff with adoration, laments the strained relationship with his mother, and grieves the death of Jeff’s mother.

I was particularly struck by this stanza speaking to his lover in “Summer”:

“You wrap your arms around me & it’s like you’re the patron saint of touch as / well as soft sunlight & soothed dogs. Or you must be the early representative / of divine holding. Or you’re both & also a boy, like me, holding on.”

I was also painfully struck by “a small book of questions: question vii” when the narrator describes his efforts to make his mother acknowledge his boyfriend and laments:

“I want to remember better. / But I want more, more of the / better to remember.”

At its heart, this collection is about the never-ending riddle of identity — race, sexuality, family identity — and also about love and grief and stubborn joy in the face of that grief. Many people will find something in this collection, some empathy, some resonance, some connection. But, if you are a) queer, b) Asian-American, or c) have parents who routinely disappoint you while also being disappointed IN you (bonus points if, like me, you have all three!) then this book was made for YOU SPECIFICALLY. And you definitely need it.